More Information

Submitted: March 21, 2024 | Approved: April 18, 2024 | Published: April 22, 2024

How to cite this article: Menditto L. Breast Cancer in Female. Arch Cancer Sci Ther. 2024; 8: 013-018.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.acst.1001040

Copyright License: © 2024 Menditto L. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Panic/hypochondria; Depression; Induced menopause; Stiffness; Hypercontrol; Multidisciplinary approaches

Abbreviations: PDTA: Therapeutic and diagnostic planner activities

Breast Cancer in Female

Lorena Menditto*

Human Science Department, Lumsa, Italy

*Address for Correspondence: Lorena Menditto, Human Science Department, Lumsa, Rome, Italy, Email: [email protected]

Anxiety is also a very common disorder, both in patients and their family members. Anxiety and stress can compromise the quality of life of cancer patients and their families. Feelings of anxiety and anguish can occur at various times of the disease path: during screening, waiting for test results, at diagnosis, during treatment or at the next stage due to concern about relapses. Anxiety and distress can affect the patient’s ability to cope with diagnosis or treatment, frequently causing reduced adherence to follow-up visits and examinations, indirectly increasing the risk of failure to detect a relapse, or a delay in treatment; and anxiety can increase the perception of pain, affect sleep, and accentuate nausea due to adjuvant therapies. Failure to identify and treat anxiety and depression in the context of cancer increases the risk of poor quality of life and potentially results in increased disease-related morbidity and mortality [1]. From all this we deduce the need and importance of dedicated psychological and psychiatric support for these patients within the Breast Unit. The fact that the psycho-oncologist who is dedicated to the care of patients with breast cancer must be an integrated figure in the multidisciplinary team of the Senological Center and not an external consultant is enshrined in the same European Directives that concern the legislation concerning the requirements that a Breast Unit must have in order to be considered a Full Breast Unit (Wilson AMR, et al. 2013).One of the most complex situations you find yourself dealing with is communication with the patient. This communication is particularly complex in two fragile subpopulations that are represented by women. [Menditto L. T (Tirannie) Cancer of the Breast. Am J Psychol & Brain Stud, 2023; 1(1):26-30].

Psychological aspects

How can a 30-40 year old female who is currently working, studying, in love, thinking about motherhood, or already has a family feel about this sudden change of course?

Breast cancer is an extremely prevalent disease in the Western world, and thanks to the evolution and efficacy of treatments and the consequent improvement in life expectancy, the population of patients who survive the disease in the long-term is now very significant. There are an estimated 2.2 million patients in the United States who are long-term survivors of breast cancer, and approximately 25% - 30% of patients who receive a new diagnosis of breast cancer are under 50 years of age [2].

Thus, a large segment of the population in an active phase of life is faced with issues related to an often complex and articulated diagnostic-therapeutic and rehabilitation pathway and to socio-occupational, emotional and functional recovery after the acute phase of the disease. Improvements in early diagnosis and the therapeutic arsenal have over the past decades given considerable emphasis to these specific Themes, associated with a shift in the attention of the medical and scientific community from adverse treatment events in the short term, to sequelae that may persist for a long time after the completion of treatment and have a negative impact on the patient’s quality of life.

Psychological aspects

The WHO defines Quality of Life as ‘the subjective perception that an individual has of his or her position in life, in the context of a culture and a set of values in which he lives, including in relation to his or her goals, expectations and concerns’ (World Health Organization, 1948). In a more pragmatic and operational way, the quality of life can be described by a series of areas or dimensions of human experience that concern not only the physical conditions and symptoms, but also the ability of a person to function, from a physical, social, psychological point of view and to derive satisfaction from what he does, in relation to both his own expectations and his own ability to accomplish what he wants. Therefore, the quality of life contemplates the concept of general well-being that is declined as physical and functional well-being, as well as emotional and social.

To date, there are few studies that have taken into account Quality of Life as a primary outcome measure in breast cancer.

There are general aspects that can affect the quality of life of people with cancer. These are primarily the fear of death, the abrupt interruption of life projects, changes in body image and self-esteem, changes in the social role and lifestyle, as well as work, legal and financial concerns. The quality of life of patients with breast cancer also has various peculiar aspects. First of all, the specific problems related to the woman’s health, such as the symptoms of early menopause induced by treatments, complications related to the sexual sphere, issues related to the change in body image and fertility. Then the long-term complications related to treatments, such as the Lymphedema, chronic fatigue, insomnia and pain. Of no lesser importance, the psycho-social aspects such as depression, anxiety, social problems including changes in family and work roles. Finally, the need to undergo follow-up to identify any recurrences in a timely manner [3]. Depression represents a central node in the quality of life in oncology. People facing a cancer diagnosis and their family members may experience various levels of stress: depression not only afflicts the patient himself, but also has a strong impact on families. A recent English survey has shown that, among many factors, maternal depression is the strongest predictor of emotional and behavioural problems in the children of women with breast cancer [4]. A recent Italian study of over 300 patients 5 years after the diagnosis of cancer evaluated whether the quality of life of these people was comparable to that of the general population and it was found that the lower levels of quality of life understood as physical and emotional functioning are more strongly associated with psychological conditions (eg anxiety and depression) than with socio-demographic variables or those related to the characteristics of the carcinoma itself [5].

Depression is a disabling syndrome that afflicts about 15% - 25% of cancer patients [6-8]. A systematic rewiew on the prevalence of depression in adults with cancer reports the following estimates: 5% to 16% in outpatients, 4% to 14% in hospitalized patients, 7% to 49% in patients undergoing palliative care [9]. Studies that used experienced interviewers (psychiatrists or clinical psychologists) reported lower prevalence estimates. It should be noted, however, that of the 66 studies detected, only 15 (23%) met the quality criteria, so the prevalence estimates are inaccurate [10]. Another recent work assessed the prevalence rates of anxiety and depression after.

A diagnosis of cancer, taking into account the type of cancer and the age and gender of the patients. Patients with lung, gynecological and hematological carcinomas report the highest rates of psychopathology. The prevalence of anxiety and depression is higher in females, and for any type of cancer, the prevalence rates are double or triple those detected in males. Female patients under the age of 50 report clinical or subclinical levels of anxiety in more than 50% of cases [11]. It is actually very important to know how to recognize a real depression. In fact, sadness and pain are normal reactions and all people experience these reactions periodically, even more so after a diagnosis of carcinoma. But, precisely because sadness is common, it is important to distinguish a normal sadness from a depressive disorder. The characteristics of true depression should be well present in the minds of industry players at various levels. It is important to consider that depression is a disorder that is often under-diagnosed even in the general population and that the depressive symptoms that occur at the time of diagnosis of cancer may represent a pre-existing condition and therefore require separate evaluation and treatment. A critical aspect in cancer treatment is precisely the recognition of the levels of depression present and the determination of the appropriate level of intervention, ranging from short counseling to support groups, to psychotherapy, to pharmacological treatment [1]. So it is important not to overestimate, intervening too early or too incisively, but also not to underestimate. Indicators that suggest the need for early intervention are: previous history of depression; poor social support [e.g., single status, scarcity of friendly relationships, a solitary or hostile work environment], evidence of persistent irrational, excessive or Unrealistic about the disease, a more serious prognosis, greater cancer-related dysfunctions.

Anxiety is also a very common disorder, both in patients and their family members. Anxiety and stress can compromise the quality of life of cancer patients and their families. Feelings of anxiety and anguish can occur at various times of the disease path: during screening, waiting for test results, at diagnosis, during treatment or at the next stage due to concern about relapses. Anxiety and distress can affect the patient’s ability to cope with diagnosis or treatment, frequently causing reduced adherence to follow- up visits and examinations, indirectly increasing the risk of failure to detect a relapse, or a delay in treatment; and anxiety can increase the perception of pain, affect sleep, and accentuate nausea due to adjuvant therapies. Failure to identify and treat anxiety and depression in the context of cancer increases the risk of poor quality of life and potentially results in increased disease-related morbidity and mortality [1].

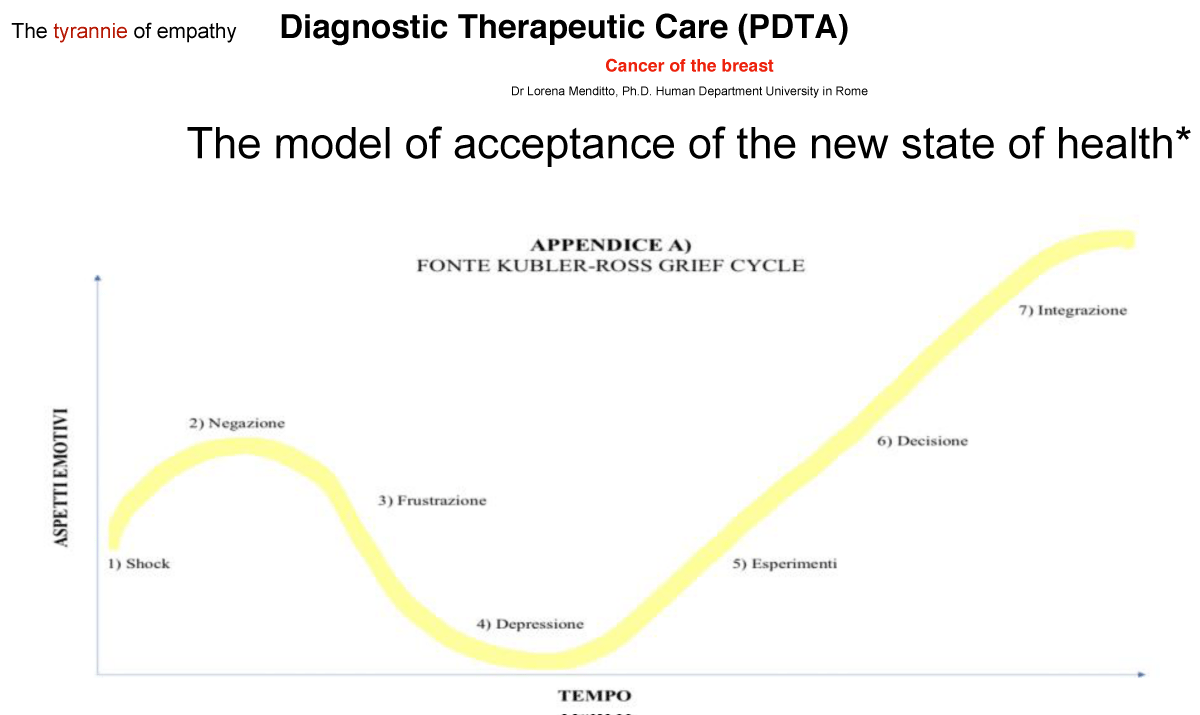

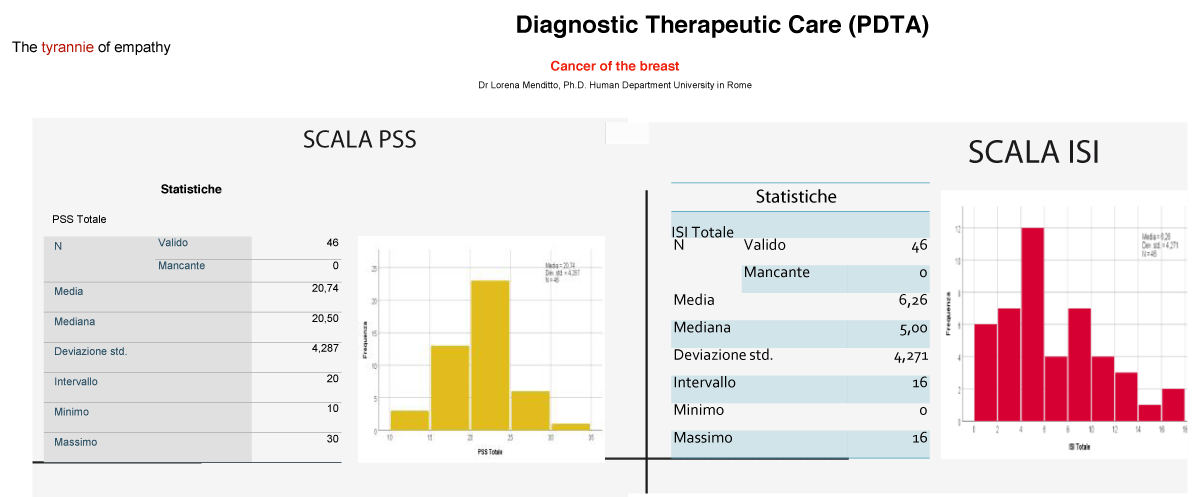

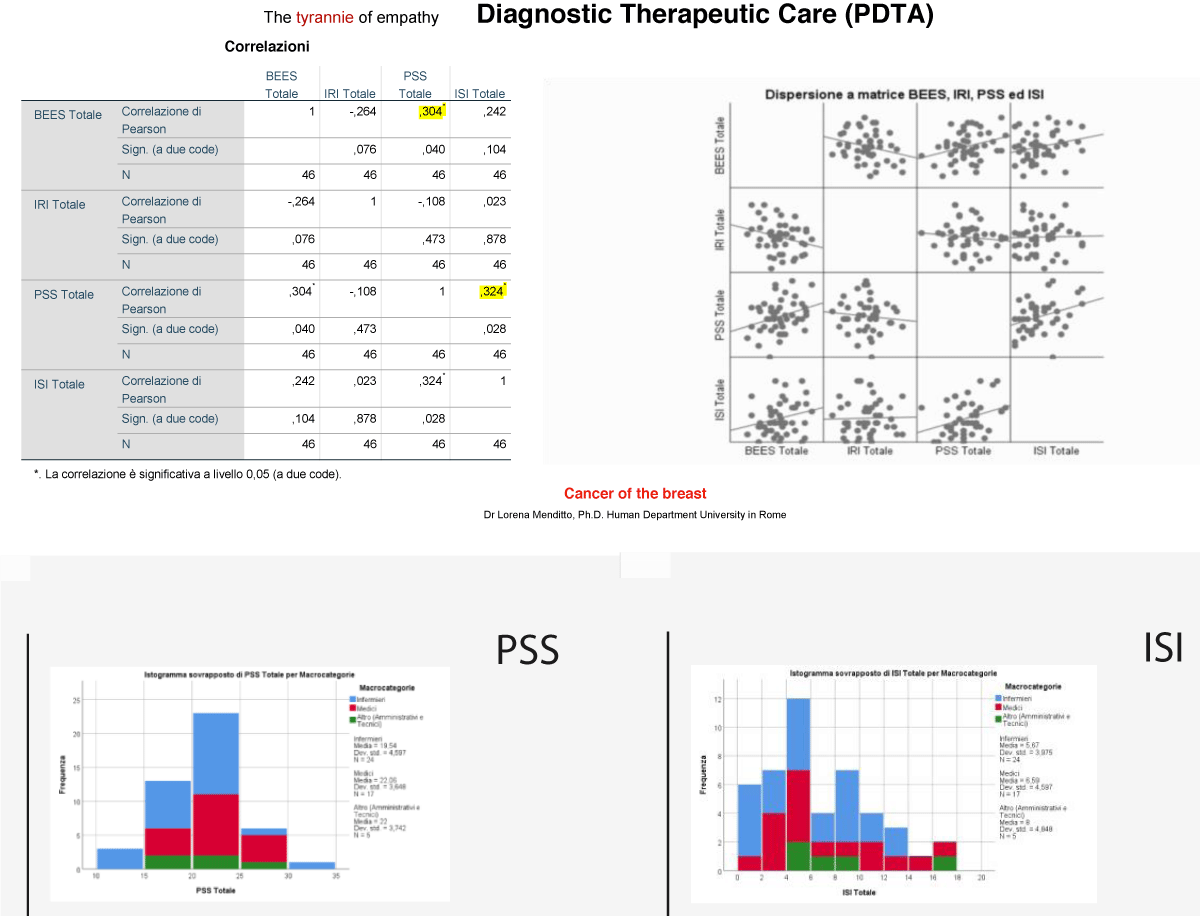

From all this we deduce the need and importance of dedicated psychological and psychiatric support for these patients within the Breast Unit. The fact that the psycho-oncologist who is dedicated to the care of patients with breast cancer must be an integrated figure in the multidisciplinary team of the Senological Center and not an external consultant is enshrined in the same European Directives that concern the legislation concerning the requirements that a Breast Unit must have in order to be considered a Full Breast Unit (Wilson AMR. et al. 2013). One of the most complex situations you find yourself dealing with is communication with the patient. This communication is particularly complex in two fragile subpopulations that are represented by women (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1: The model of acceptance of the new state of health - Kubler Ross Grief Circle.

Figure 2: Diagnostic Therapeutic Care PDTA -Scale of stress and Index of Irritability.

Figure 3: Diagnostic Therapeutic Care PDTA - Scale of stress Perceived and Sleep Index.

Protocol 1)

Depressive assestment

Anxiety - Depression – Stress PTDS (ADPTDS)

1) MADRS - (Montgomery Albery Depression) measures the severity of mood disorders

2) HAD - (Hospital Anxiety Scale)

3) Perceived stress

4) BECK’s scale

5) HAMILTON

Protocol 2)

Cognitive assessment

Apathy – CBA(H) – Frustration

1. PFS - Picture Frustration Study

2. STAY - State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Form Y

3. BAI – Beck Anxiety Inventory

4. CBA-H - Cognitive Behavioural Assessment – Forma Hospital

5. SCL-90-r –Symptom Checklist-90-R

Protocol 3)

Defense Mechanisms

(DMI – PFS – PoMS)

1. DMI – Defense Mechanisms Inventory – Form for Adults

2. PFS – Picture-Frustration Study

3. PoMS – Profile of Mood States

Protocol 4)

Psychological Treatment

(PTI - PCL-r)

1. PTI – Psychological Treatment Inventory

2. PCL-r – Hare Psychopathy Checklist – Revised: 2nd Edition

Protocol 5)

Parenting Stress

(PSI - EPQ-r – CBI)

1. PSI – Parenting Stress Index – Short Form

2. EPQ-r – Eysenck Personality Questionnaire – Revised

3. CAREGIVER BURDEN INVENTORY (CBI)

Young and women with metastatic or locally advanced forms

Young patients are more vulnerable to psycho-social distress because of their stage of life development: they can be single, married, young mothers of young children or adolescents, variously engaged in work and career; the multiple demands of the disease are stratified on top of the multiple needs typical of this stage of life. Young woman with breast cancer may become more vulnerable to psychological morbidity, in an attempt to manage multiple stressors [12]. She will have to address, for example, the symptoms of an early menopause induced by adjuvant therapies (chemo and hormone therapy) and it will be essential to help her in the management of these problems at various levels through information, psycho-education, psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, when necessary.

Sexuality during and after the tumor

The psychological impact of the oncological disease is always strong, in all people, of all ages, of all kinds, of all social and religious affiliations. The age groups with the highest incidence of cases of breast cancer are, however, varying: although the peaks of incidence continue to occur from the age of 50, more and more patients under the age of 40 and between 40 and 50 years, see this type of pathology diagnosed [Associazione Italiana Oncologia Medica-AIOM and Associazione Italiana Registri Tumori- AIRTUM, 2015]. But how to relate to a young woman with breast cancer? Of course depression, ‘dark evil’ is terrible and can destroy your life, it can lead you to wish you don’t live anymore. But cancer, especially when you’re 30 or 40 years old, hits you in the back while you’re living and want to live. And more than ever.

Talking in terms of diagnosis, therapies is reductive, insufficient, inadequate. How do you communicate this diagnosis to a young woman and then give her valuable support in coping with the upheaval of her projects, social, work, family balances? How can you deal with temporarily or permanently frustrated needs (love life, sexuality, motherhood, body image)? And finally, how can you promote the expression of emotions of fear, anger, discomfort and help this woman to understand when her reaction to the disease is not physiological for the extent of the symptoms and for the duration and needs specialist help?

I firmly believe that the need to create a dedicated psychological and psychotherapeutic support path, in the context of a breast-unit, has the objective of answering these questions and satisfying these needs.

The diagnosis of breast cancer unexpectedly breaks into a woman’s life resulting in a fracture in the plot of that existence. Nothing is the same as before since that day. The feeling is to find yourself unexpectedly in front of an enemy... a sneaky enemy, who threatens your integrity as a woman, partner, mother, person who works and moves in the society in which he lives. Breast cancer is the most common cancer pathology in the female sex: it is estimated that, in Italy, about 48,000 new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed every year, 1% of which affect the male sex. [Italian Association of Medical Oncology-AIOM and Italian Association of Tumor Registries-AIRTUM, 2015]. Concerns related to body image, self-esteem, reduced sexual satisfaction; the management of the desire to have a pregnancy and the discussion of the possibilities of preserving fertility are other issues to be addressed with these women and about which to provide information, support and understanding.

In women with metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer, the issues related to the progression of cancer are of greater interest: pain; fatigue, having to face the fear of death. In a recent meta-analysis of the Cochrane Collaboration carried out on over 1300 women, the impact of various psychological interventions (group, cognitive behavioral, supportive-expressive groups) on outcome measures, both psychologicalpsychosocial, and survival-related (Mustafa M, et al. 2013). It has been seen that psychological interventions are able to improve not only the psychological well-being of the woman, but also to affect physical well-being, for example by reducing pain and determining, according to these preliminary data, also an indirect effect of improving survival (Mustafa M, et al. 2013).

The role of the psycho-oncologist in the senological field is now made more complex, but certainly also more stimulating by the fact that the psychological implications of breast cancer, once linked almost exclusively to survival, the demolitional characteristics of surgery and the toxic characteristics of adjuvant treatments, are currently more influenced by the complexity and duration of the therapies, their degree of integration, the possibility of choosing the best treatment among the various options available. The diagnostic and therapeutic path of a woman with breast cancer, much less traumatic than in the past, is however long and complex due to the need for numerous investigations before being able to reach the longawaited eradication of the disease; moreover, precisely because of the characteristics of today’s care, active participation in decisions by patients is necessary, which, if it is to be considered (and usually this usually happens) positively, has an anxious impact on some of them, doubtful about the various therapeutic alternatives. If most women certainly appreciate (sometimes ‘claim’) this participation in decision-making processes, they however, it is another share that goes into crisis because it would prefer not to participate in the decisionmaking process but find it ‘drun from the top’.

In conclusion, the role of the psycho-oncologist in the senological setting is very complex and fascinating, given the complexity of the scope in which this figure moves and the issues he has to address, communicating and collaborating with the multidisciplinary medical team at various levels. If properly managed and enhanced, this type of activity can act as an element of cohesion for the team and be central to the alignment between medical and patient teams.

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Feb;12(2):160-74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. Epub 2011 Jan 19. PMID: 21251875.

- Manopola MT. The influence of endocrine effects of adjuvant therapy on quality of life in younger breast cancer survivors. The oncologist. 11(2): 96-110.

- Ganz, PA, Yip, CH, Gralow, JR, Distelhorst, SR, Albain, KS, Andersen, BL, Anderson BO. Supportive care after curative treatment for breast cancer (survivorship care): Resource allocation in low- and middle-income countries. A consensus statement from the Breast Health Global Initiative 2013. Breast. 2013; 22(5): 606-615.

- Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Flaiban C, Giovannini L, Carlucci M. Mood states in long-term cancer survivors: an Italian descriptive survey. Support Care Cancer. 2016 Jul;24(7):3157-64. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3134-1. Epub 2016 Mar 1. PMID: 26928442.

- Annunziata MA. Psychosocial assistance in oncology: the Italian reality. Health and Society. 2015/2.

- Henriksson MM, Isometsä ET, Hietanen PS, Aro HM, Lönnqvist JK. Mental disorders in cancer suicides. J Affect Disord. 1995 Dec 24;36(1-2):11-20. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00047-x. PMID: 8988260.

- Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM, Carnicke CL. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983; 249 (6), 751-757.

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K. Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):17-21. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh023. PMID: 15263036.

- Walker J, Holm Hansen C, Martin P, Sawhney A, Thekkumpurath P, Beale C, Symeonides S, Wall L, Murray G, Sharpe M. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2013 Apr;24(4):895-900. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds575. Epub 2012 Nov 21. PMID: 23175625.

- Walker J, Sawhney A, Hansen CH, Symeonides S, Martin P, Murray G, Sharpe M. Treatment of depression in people with lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2013; 79 (1), 46-53.

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012 Dec 10;141(2-3):343-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. Epub 2012 Jun 21. PMID: 22727334.

- Alicikus ZA, Gorken IB, Sen RC, Kentli S, Kinay M, Alanyali H, Harmancioglu O. Psychosexual and body image aspects of quality of life in Turkish patients with breast cancer: a comparison between breast-conserving treatment and mastectomy. Tumor Journal. 2009 ; 95 (2), 212-218.

- Lima SR, Junior VFV, Christo HB, Pinto AC e Fernandes PD. . In vivo and in vitro studies on the antitumor activity of Copaifera multijuga Hayne and its fractions. Phytotherapy Research: An international journal dedicated to the pharmacological and toxicological evaluation of natural product derivatives. 2003; 17(9): 1048-1053.

- Petit JY, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, Bertolini F, Clough KB, Sarfati I, Gale KL, Macmillan RD, Rey P, Benyahi D, Rietjens M. Safety of Lipofilling in Patients with Breast Cancer. Clin Plast Surg. 2015 Jul;42(3):339-44, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2015.03.004. Epub 2015 Apr 28. PMID: 26116939.

- Tibaldi A. The animal tumor registry: do you have an idea what it is for?. Aivpa Journal. 5(3): 20-23.

- Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Vogel J, Carroli G, Lumbiganon P, Qureshi Z, Costa MJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa Y, Nafiou I, Neves I, Wolomby-Molondo JJ, Bang HT, Cheang K, Chuyun K, Jayaratne K, Jayathilaka CA, Mazhar SB, Mori R, Mustafa ML, Pathak LR, Perera D, Rathavy T, Recidoro Z, Roy M, Ruyan P, Shrestha N, Taneepanichsku S, Tien NV, Ganchimeg T, Wehbe M, Yadamsuren B, Yan W, Yunis K, Bataglia V, Cecatti JG, Hernandez-Prado B, Nardin JM, Narváez A, Ortiz-Panozo E, Pérez-Cuevas R, Valladares E, Zavaleta N, Armson A, Crowther C, Hogue C, Lindmark G, Mittal S, Pattinson R, Stanton ME, Campodonico L, Cuesta C, Giordano D, Intarut N, Laopaiboon M, Bahl R, Martines J, Mathai M, Merialdi M, Say L. Moving beyond essential interventions for reduction of maternal mortality (the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health): a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2013 May 18;381(9879):1747-55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60686-8. PMID: 23683641.